I was once fly-posting in a very salubrious area of London. I was advertising a show by our film-making society. I was aware of the local by-laws against fly-tipping and chose to do it after dark. I carried a pot of paste and the posters in a shoulder bag. I was pasting on to a lamp-post when I heard a shout. I saw a group of well-healed gentlemen emerging from an exclusive club frequented by politicians and other establishment figures a few hundred yards away. A stout gentleman was pointing in my direction and I could see the faces turned towards me in the lamplight. A moment of fear soon changed to one of excitement and then exhilaration as I slung the bag on to my shoulder and slunk into the night. Is that how Martin Luther felt in 1517 when he nailed to the door of the church in Wittenberg his challenge to papal authority?

Gutenberg had invented moveable-type printing a hundred years before Luther’s fly-posting episode and by doing so had put a weapon into the hands of ordinary people which continues its effect to this day. As I type this I do not take for granted the journey I am making from those Cro Magnon artists. In one keystroke I can send this blog around the world in seconds for millions (hopefully) of people to read. Unfortunately that is not going to happen – unless I mention I have a weird creature in my potting shed that makes sounds like a dolphin and looks like a python with arms and legs.

State regimes from China to the Middle East are spending vast resources to combat the wave of technology that puts the power of words into the hands of almost anyone. Weapons did not destroy the Soviet Union or the Berlin Wall. By the 1970’s the communists had educated a whole generation of young people beyond the limits of their state propaganda. There were television sets in shops and restaurants to keep the underpaid workers from being restless. Sure, the cameras were carefully focussed when recording overseas news – but they saw the way Westerners were dressed, they saw the many cars when only Party officials had them in Russia and they glimpsed the number of shops that were always busy when the old department stores in Leningrad had long empty counters. And they taught their pupils languages; the airport staff spoke excellent English when the selected managers and receptionists in the tourist hotels struggled to form a sentence. And those educated youngsters listened to pop music from Britain and the US with their liberating anarchic lyrics and their references to New York, New York and London swings like a pendulum do. Now the flood of influence is unstoppable. There is nowhere, not even Pyong Yang, that is an island to iteself. Except for dropping television sets, McDonald burgers and i-phones onto countries like North Korea, words are still the best weapons against regressive regimes and the genius of Alan Turing and Konrad Zuse gives everyone the chance to use them.

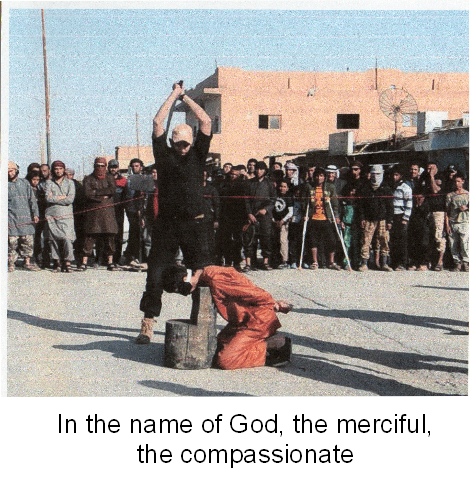

But are words mightier than the sword? From my choice of logo you would think that I subscribe to the Proverb. However, I am not entirely convinced, as words as a weapon depend for their effect on the ability of the victim to understand them. At primary school there was a playground chant; “Sticks and stones might break my bones but words can never hurt me.” I have recieved a bloody nose for relying on that but if I had been Oscar Wilde I might have responded with “If I had a brain like yours I would donate it to an animal charity” which might have had a more lasting effect than a bloody nose. Let us test the theory. The most powerful images to incense the masses were the online beheadings by Mohammed Emwazi (Jihadi John) of James Foley, Steven Sotloff, David Haines and Alan Henning. World leaders reacted with words to describe their feelings; Appalled. Brutal. Cowardly, Heinous. Wicked. Abomination but none of these words adequately countered the images. Was then the sword mightier than the pen? on the face of it that would seem to be the case. But if we consider what drove the arms and brain of Emwazi to commit such atrocities we might take a different view. If we believe the rhetoric of Emwazi and other jiahists then somewhere along the line it was the words of the holy Koran that were responsible for their actions – or, at least, its interpretation. And if we put the images and the words of the Koran together are the words not mightier than the sword?